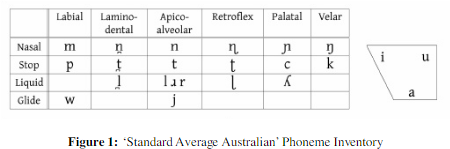

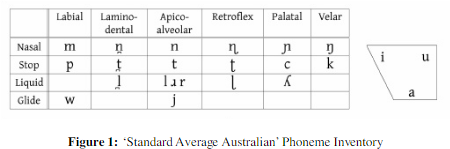

The indigenous languages of Australia have striking similarities in their phoneme inventories. Most have no fricatives, and none, as far as I know, have sibilants. Australian languages tend to have retroflexes (one exception is Bandjalang, which has only 12 consonants), palatals, contrastive dentals and alveolars, and several laterals and rhotics. Gasser and Bowern (2013) provide a chart of a ‘Standard Average Australian’ phoneme inventory:

Individual languages, of course, diverge from this pattern. Some have a voicing contrast in plosives, although this may really be a gemination contrast: Gasser and Bowern report that 59% of languages with a plosive voicing contrast collapse it initially. (Cf. the Proto-Basque fortis-lenis contrast: in plosives, this has become a voicing contrast, but fortis consonants could not appear word-initially and lenis consonants could not appear word-finally.) Over half have contrastive vowel length.

But there is much less difference across inventories in Australia than in most parts of the world. For example, Guugu Yimidhirr, the source of the English word ‘kangaroo’, differs only in having only one lateral (the apico-alveolar /l/) and a length contrast in its vowels. Dyirbal, the language whose noun class system inspired the title of George Lakoff’s Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things, is somewhat more divergent: its only retroflex consonant is the flap /ɽ/, its only lateral is the apico-alveolar /l/, and its only laminal consonant series is palatal.

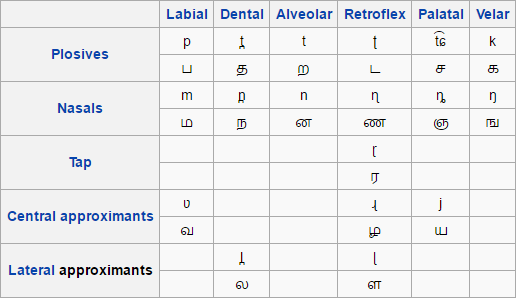

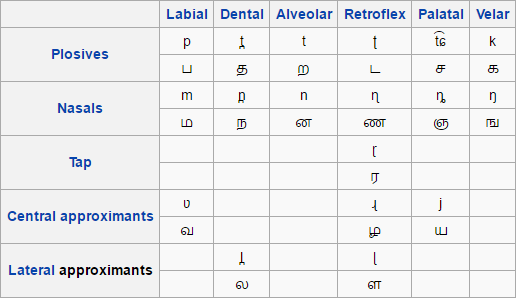

What happens if we compare Standard Average Australian to Tamil?

The vowel inventory of Tamil differs significantly from that of SAA—Tamil has the mid vowels /e o/, the diphthongs /ai au/, and a length contrast in monophthongs—but the underlying consonant inventory is almost identical. The only significant differences are in the liquids: the rhotics are both retroflex, and Tamil has fewer laterals than SAA.

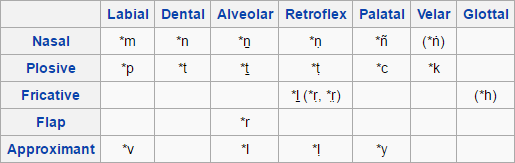

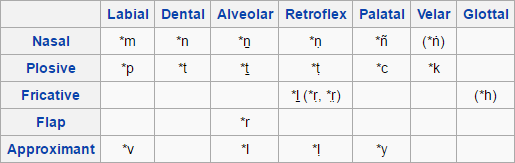

Looking to modern languages to try to gain information on ancient patterns is of course untenable as serious methodology, but it’s at least suggestive. Here’s Proto-Dravidian.

The velar nasal, present in all Australian languages in Gasser and Bowern’s sample, may not have been phonemic in Proto-Dravidian, but the general similarity is clear. I know of no other non-Australian language family that so closely follows the typical Australian language pattern, so, although I have no suggestion as to the causal relation here, no hypothetical scenario of ancient contact between India and Australia that could have spread this pattern from one place to the other, I suspect that one exists.

Interestingly, a ban on word-initial retroflexes is common among Australian languages, and Proto-Dravidian (like some languages of Western Australia, although I don’t know when this restriction developed) banned all apicals from word-initial position.

Pingback: The Dravidian-Australian connection? | Reaction Times

Genetic studies show similar indications see e.g. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-21016700

Thought you might be interested (HT: DeBoer) Tom Wolfe on Chomsky in Harper’s. I don’t know where a free copy is, yet.

Language Log says it’s an excerpt from a book. (Tom Wolfe writing a book about linguistics — Toto, I don’t think we’re on the alpha timeline anymore.) I’ll buy it when it comes out.

I don’t do syntax, but the Everett smackdown narrative is premature. Uli Sauerland thinks Piraha has complex clauses.

Phonemic inventory may indeed be more stable over time than the individual phonemes are. English allows an initial stop to be preceded by /s/ (which neutralizes the voiced/unvoiced contrast) and followed by a “liquid”, either /l/ or /r/; but /l/ cannot follow a dental. Pay, bay, spay, pray, spray, play, day, dray, stay, stray, and so forth. Something like this inventory is found in most of Indo-European (although with so many exceptions as to weaken my claim), in contrast to the numerous language groups that forbid consonant clusters.

The restriction on /l/ following a dental isn’t universal to Indo-European (Old Latin stlocum > Lat. locum) — or even to English. Some UK dialects apparently have kl > tl.

That said, I don’t know of any IE languages that prohibit consonant clusters, or any Polynesian languages that allow them, so.